Growth management refers to anticipating and guiding growth and development to achieve community priorities—whether they are focused on efficient use of land, a revitalized downtown, promoting rural lifestyles, or encouraging industrial growth. Growth management focuses on how to achieve these priorities while controlling their costs and balancing the growth generated through development (and its associated tax revenues) with activities and costs needed to ensure adequate capacity of roads, schools, and other public facilities and services.

Why is this important to your community?

The consequences of unmanaged, fragmented growth can include congested roads, overcrowded schools and infrastructure systems, mismatches between housing, water demand and available sewer infrastructure, and fiscal imbalances—where the cost to serve new development exceeds the revenues it generates, thus burdening existing taxpayers. Growth management seeks to proactively guide development into patterns that reduce costs of services or help increase property value. This is often done by promoting growth in areas where infrastructure and public services systems are in place and of sufficient capacity, or where improvements to increase system capacities can be made cost effectively and in a timely manner. Effective growth management produces land use patterns and infrastructure investments that are mutually-supportive, provide for more efficient development of public facilities, less “wasted land,” and stronger protection of community character and fiscal stability. In short, managed growth produces public systems that are synergistic and work together, rather than those that work at cross-purposes.

Where is it appropriate to use?

What priorities does it address?

What other tools are related?

How does it work?

Growth Management involves a suite of tools that regulate the development of land and other resources such as water and sewer systems and transportation networks to support staged expansion of public facilities and services to meet the demands associated with new growth and development. The “staging” of growth and associated facilities and service is extremely important—even the best “growth management approach” that includes mismatched time frames on compact housing development and transit implementation can result in traffic congestion. Specific growth management tools include the following:

Comprehensive Plans

Comprehensive Plan Implementation Tools

- Zoning Ordinances or District Maps: These regulations and laws define how lots and properties within a specific zone can be used or developed. Districts may include residential, commercial, industrial, or mixed use. Regulations concerning lot size, placement, bulk, and height are often included to ensure that desirable characteristics of each district or zone are maintained. See Inclusionary Zoning and Mixed Use Development and Design Guidelines tools.

- Neighborhood/Sub-Area Plans: Subarea plans are detailed plans prepared for a smaller geographic area within a community. The areas can encompass neighborhoods, corridors, downtowns, or other types of special districts that show cohesive characteristics. Also referred to as sector, small area, character area, or specific area plans, subarea plans include a greater level of detail than a comprehensive plan, but deal with many of the same topics. See Subarea Plans tool.

- Downtown Revitalization Plan: Traditional downtowns were once the business center of communities. Following suburbanization in the latter half of the 20th century, these areas faced competition from suburban shopping centers and malls. Despite this, a growing percentage of the population now prefers walkable centers with compact development. Downtown Revitalization Plans focus on creating healthy downtowns that reflect the needs of the community by addressing existing weaknesses and building on strengths. These plans seek to direct investment and development into the traditional downtown core. Turning Around Downtown: Twelve Steps to Revitalization

- Historic District Revitalization Plan: Protecting historic districts helps to maintain and revitalize a community’s core, keeping the tax base strong where services are already established. The responsibility for protection of historic and culturally significant properties lies mostly within local governments. National and state resources and programs provide additional resources and incentives such as grants and tax credits for revitalization, renovation, and planning. By establishing a local historic district, residents and property owners can protect investments made in the district, and generally can expect their property values to appreciate at a faster rate than similar non-designated neighborhoods according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. See Historic District Designation tool.

- Main Streets Program: Small Town Main Street Programs are designed to give small communities the tools, leadership, and organizational framework to bring economic vitality back to their downtowns. The National Trust for Historic Preservation established the Main Street Program in 1980 to help small communities throughout the United States accomplish economic resurgence through the reuse of commercial buildings located in historic downtowns. Main Street programs have been shown to result in economic revitalization, fostering small business growth, finding new life for historic buildings, and spurring further infill development and resurgence adjacent to downtowns. See Main Street Programs tool.

- Strategic Parking Plan: Increasing density in downtown areas or city centers often means restructuring parking to allow for the development of underutilized or undeveloped land. Strategic Parking Plans is a framework that helps communities clarify the direction and approach to parking in urbanized areas. These plans balance the need for parking with the desire for denser development patterns and greater walkability. The Strategic Parking Plan

- Parks and Recreation Plans: Parks and Recreation Plans gather input from citizens about what types of park and recreational amenities they would like to see within their community. These plans lay a framework for future investment in parks and recreation systems over a 5 to 10 year period. Oklahoma City Parks Master Plan Mecklenburg County 10 Year Master Plan for parks and recreation

- Capital improvement Plan (CIP): CIPs identify key projects and provide a detailed schedule and financing plan/budget for investments made by a local government entity (e.g., school district, parks and recreation, utilities department). These are typically short-range plans encompassing a period of less than 10 years. Capital Improvement Plan

- Metropolitan Transportation Plans (MTPs) or Community Transportation Plans (CTPs) adopted by MPOs, RPOs, or the State Departments of Transportation: MTPs, transportation plans required by federal law, have a number of planning requirements that includes design concepts, estimated transportation forecasts, and a financial plan. These plans are required to address issues over a 20-year period. CTPs address all modes of transportation, including trains, public transportation, bicycles, pedestrians, and vehicles, for a specific community. Guidance for Crafting CTP Vision Goals

Interlocal Communication, Collaboration or Agreements

Sharing of GIS Data (or data in other forms) with adjacent community to align plans

Urban Services Boundaries

- Urban Service Area (Tier 1) – that area that is largely developed and fully served by existing public facilities and services, and where infill and redevelopment can be accommodated and may be encouraged.

- Future Urban Service Area (Tier 2) – a partially developed, contiguous fringe area designated to accommodate future growth, where infrastructure and public services may be partially available and system capacity expansions are planned.

- Rural Area (Tier 3) – Remote areas where infrastructure and public services expected in urban and suburban locations are not available, and where development would be premature and unnecessary to accommodate projected population growth. Investments in schools or other facilities that might prompt premature development should be avoided.

Adequate Public Facilities Ordinances

An Impact Fee is a tool to ensure that new development “pays for itself” by charging a fee to cover the costs to expand schools, widen roads, extend water and sewer lines, provide adequate open space and expand public safety service areas. Following a fiscal analysis of public facility and service costs in relation to local property and sales tax revenues, identified funding gaps are the basis for establishing appropriate impact fees. The one-time fee is then established on a per unit basis for residential development and on a square footage basis for non-residential development. South Carolina has state enabling legislation that allows municipalities to collect impact fees as a funding source. North Carolina does not have state enabling legislation allowing the widespread usage of impact fees. However, impact fees can be authorized for individual jurisdictions by the legislature.

South Carolina Code of Laws State Enabling Acts

Ready to get started?

Using the Tool

A Growth Management Policy Framework should ideally be created as a component of a comprehensive plan, which could include the following steps.- Assemble a Task Force of departments concerned with or affected by growth, and include other non-governmental leaders from the community, as a guiding or advisory body.

- Identify the community’s projected population over the next 10, 20, or 30 years, and if possible, include projected job growth (this will be much harder and open to much discussion)..

- Using that information for background, start a community wide visioning effort to identify the community’s values for community character and quality of life given that projected population and job growth. Don’t forget that the community cares as much about jobs, transportation, parks, and schools as they do about land use—so include opportunities for the community to comment on their vision for growth (or remediation) in those areas as well. This also lays the ground work for the “comprehensive” nature of the planning process.

- Utilize land use modeling tools to “allocate” growth geographically based on factors such as zoning, current development trends, accessibility, availability or proximity to infrastructure and schools, and the presence of environmental or other factors that could act as constraints on development. Create a “trend” scenario, and alternative scenarios based on public input, that are all evaluated against the community’s vision and by considering the costs to provide infrastructure and impacts on farmland and open space.Share the results of the various scenarios with the public, using information on fiscal impacts as well as impacts on community character and quality of life using metrics such as travel times, acres of open space lost, etc. Identify a preferred or optimum scenario.

- Now compare everyone’s local plans and strategies—transportation, water/sewer, broadband access, economic development, housing, parks and recreation, agricultural, schools—against the preferred or optimum scenario, if that has not been done throughout the process. What will be required for individual departmental plans to support the preferred scenario? Will infrastructure expenditures need to be redirected toward increased capacity to support infill and redevelopment? Will transit need to be planned or implemented, and by when? Will economic development efforts need to expand to include a focus on downtowns? What costs will be involved, what new strategies needed? Rather than acquiring more suburban land for new schools, should the school boards focus on new construction or rehab of existing schools?

- Using the responses to the questions above, develop an internal strategy document for departmental plan alignment, to be used as a part of the Growth Framework. It can also be used to effect needed changes to other organizations’ plans, such as what is reflected in the MPO MTP or Economic Development Commission planning.

- Identify additional growth management tools (urban growth boundaries, adequate public facilities ordinance, impact fees, utility extension policies, annexation requirements, etc.) that may be necessary to implement the comprehensive plan and address issues such as the timing of development, the staging of road and infrastructure development, and the avoidance of fiscal, infrastructure, school, and open space impacts.

- For the development of additional growth management tools secure the necessary specialized expertise (land use law, fiscal analysis, capital facilities planning) or apply suitable model ordinances.

- Involve elected leadership in every aspect of public engagement, and through periodic briefings and input sessions as scenarios are developed, tested, and alignment strategies discussed.

Partners

- Colleges and Universities

- Departments of Education / School Districts

- Developers

- Economic Development Organizations

- Elected Officials

- Landscape Architects, Planners, and Urban Designers

- MPOs, RPOs, and COGs

Where has it worked?

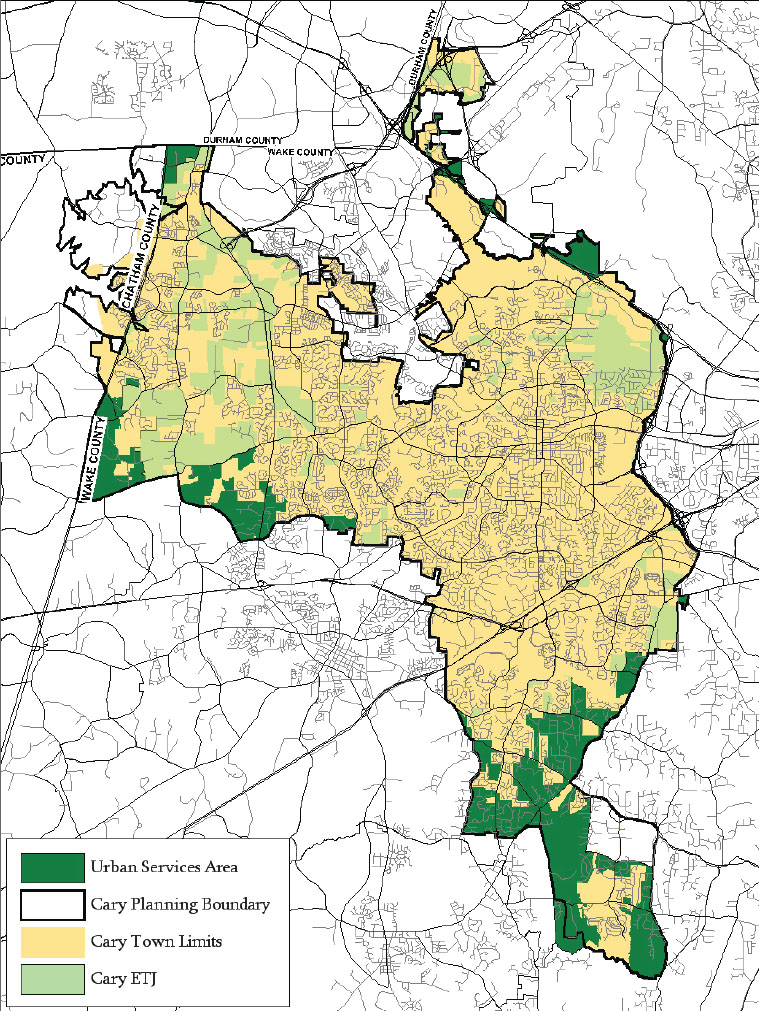

Growth Management Plan - Cary, NC

About the Program

With a strong economy, good jobs, and a high quality of life, Cary experienced rapid population growth through the 1980s and 1990s. The growth stressed the Town’s water supply and caused schools to become overcrowded and roads to become congested. To address these consequences of unmanaged growth, in 2000 the Town of Cary adopted a comprehensive Growth Management Plan that covers five aspects of growth.

- Rate and Timing

- Location

- Amount and Density

- Cost

- Quality

Specific provisions include Adequate Public Facilities for schools and roads, an Urban Services Area and annexation contiguity requirements to prevent “leapfrog” development incentives for conservation development, density incentives applicable to preferred growth areas, targeted acquisition of sensitive natural and cultural resources, high quality design guidelines and a “quality of life index” to periodically monitor the impact of growth on quality of life.

Why it works

In spite of continued high annual growth rates of 2%-6% over the past decade, the Town of Cary has succeeded in avoiding or mitigating the undesired consequences of rapid growth. The requirements for adequate public facilities and development contiguity have prevented overstressed infrastructure and services and development fragmentation that depletes open space and farmland. Likewise, incentives for higher density infill development have reduced sprawl and commuting times while expanding housing choice and promoting development walkability. With effective growth management, Cary has been able to successfully protect its character and quality of life while allowing its economy to thrive.

- Departments of Education / School Districts